|

An infographic explaining Newton's three laws of motion. © Eugene Brennan |

In this second part of a two part tutorial, you'll learn the absolute basics!

In the first tutorial, Examples of Forces in Everyday Life and How They Affect Things, we learned what force is and explored the various types of forces in the world around us.

What's Covered in This Guide?

- Newton's three laws of motion and how an object behaves when a force is applied

- Action and reaction

- Friction

- Kinematics equations of motion

|

| From the article "Examples of Forces in Everyday Life and How They Affect Things". © Eugene Brennan |

What Are Newton's Three Laws of Motion?

In the 17th century, the mathematician and scientist Isaac Newton came up with three laws of classical mechanics concerning motion of bodies in the Universe. These laws describe the relationship between the motion of an object and the forces acting on it. In physics, objects have a property called mass, measured in kg in the SI system (This stands for Système International d'Unités, the standard system of units used in science and engineering)

1. Newton's First Law of Motion: Rest or Uniform Motion

Basically, this means that if for instance a ball is lying on the ground, it will stay there. If you kick it into the air, it will keep moving. If there was no gravity, it would go on for ever. However, the external force, in this case, is gravity which causes the ball to follow a curve, reach a max altitude and fall back to the ground. Friction from air also slows it down.

Another example is when you put your foot down on the

accelerator and your car increases in speed. When you take your foot off

the accelerator, the car slows down, The reason for this is that

friction at the wheels and friction from the air surrounding the vehicle

(known as drag) causes it to slow down. If these forces were magically

removed, the car would stay moving forever.

There are three scenarios for the first law: Two for when a body is at rest and one for when it's in motion.

Body at Rest

There are two scenarios for a body at rest:

Scenario 1: No forces acting on the body

In the example of a body floating in deep space, far from any planets or stars, where it isn't influenced by gravity, it will stay in this position at rest forever. In reality of course, it will always be influenced by gravity, even at huge distances, although the effect may be tiny. In the diagram below, the body is given the symbol m, representing its mass. The body doesn't have to be in space of course, but this is an extreme example of a body so remote, that there are extremely small forces acting on it.

|

No forces act on the body, so it stays at rest. © Eugene Brennan |

Scenario 2: No net forces acting on the body.

In reality, there will always be forces acting on a body. If forces cancel out, there's no net force acting and again it stays at rest. An example is an object with mass m suspended from a rope. The force of gravity pulls down on the object. However the rope also pulls back up with a tension force. These forces cancel each other out and there's no net force.

|

| Forces cancel out and since there's no net force, the body stays at rest. © Eugene Brennan |

Body in motion

This is the 3rd scenario of Newton's 1st law. When a body is acted on by a net force, it accelerates and reaches a certain velocity. When that force is removed, it continues to travel at that velocity, unless another force acts on it. Again, the reason why we don't see this ideal behaviour happening in the real world and objects continuing to move without slowing down is because external forces act, usually friction and drag due to air. We see approximations though, so a spinning top will spin for a long time if it has a pointed foot that has little friction wit the surface on which it rests. Similarly a bowling ball or marble will roll a long way on a hard level surface without stopping.

|

| Once a body is accelerated by a force, it continues in a state of uniform motion, unless another force acts on it. © Eugene Brennan |

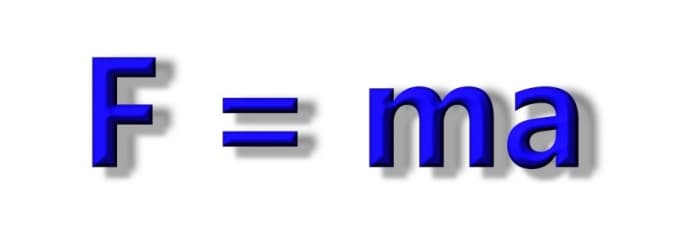

2. Newton's Second Law of Motion: Force and Acceleration

This means that if you have an object and you push it, the acceleration is greater for a greater force. So for example a 400 horse power engine in a sports car is going to create loads of thrust at the axle and accelerate the car to top speed much more rapidly than a regular engine would be capable of achieving with the same weight of car.

In the SI system of units, force is measured in Newtons (N), mass is measured in kilograms (kg) and acceleration is measured in metres per second per second (also known as metres per second squared) (m/s2)

So:

If F is the force in Newtons (N)

m is the mass in kilos (kg)

and a is the acceleration (m/s2)

Then we can write an equation for Newton's 2nd law:

F = ma

This

tells us that the mass of a body multiplied by its acceleration equals

the force applied to that body that gave it the acceleration a.

We can also rearrange the equation so

a = F / m

What does this equation tell us?

Acceleration is proportional to the applied force

So the acceleration is directly proportional to the applied force. Double the force F and a doubles. Triple the force F and a is tripled and so on.

Acceleration is inversely proportional to the mass

For larger masses, acceleration is smaller for the same force. So for example, In the equation above if we double m, a is halved.

Imagine in the example above that the sports car engine was placed into a heavy train locomotive and could drive the wheels. Because the mass of the locomotive is so large, the force creates much lower acceleration and the locomotive takes much longer to reach top speed (In the equation, F is the same, but m is below the line, so a is smaller).

|

| A force accelerates an object with a mass m.© Eugene Brennan |

Example: A force of 10 newtons is applied to a mass of 2 kilos. What is the acceleration?

F = ma

So a = F / m = 10 / 2 = 5 m/s2

The velocity increases by 5 m/s every second

|

Force = mass multiplied by acceleration. F = ma |

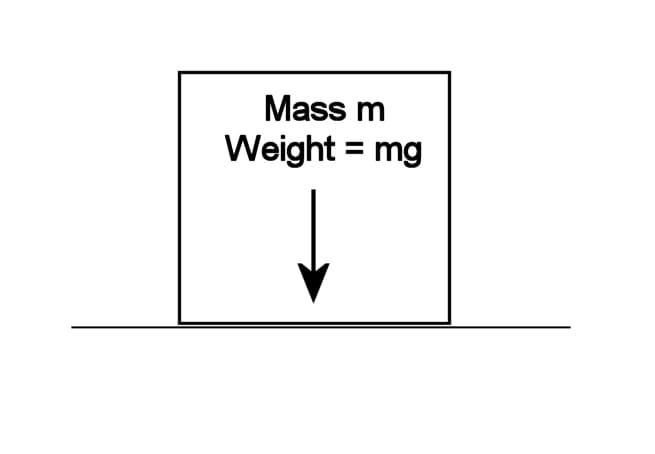

Weight as a Force

In this case, the acceleration is g, and is known as the acceleration due to gravity.

g is approximately 9.81 m/s2 in the SI system of units.

Again F = ma

So if the force F is replaced by a variable for weight we choose to be W, then substituting for F and a gives:

W = ma = mg

Example: What is the weight of a 10 kg mass?

W = mg = 10 x 9.81 = 98.1 newtons

|

Weight is the force on a mass due to gravity. The weight of a body of mass m equals mg, where g is the acceleration due to gravity. © Eugene Brennan |

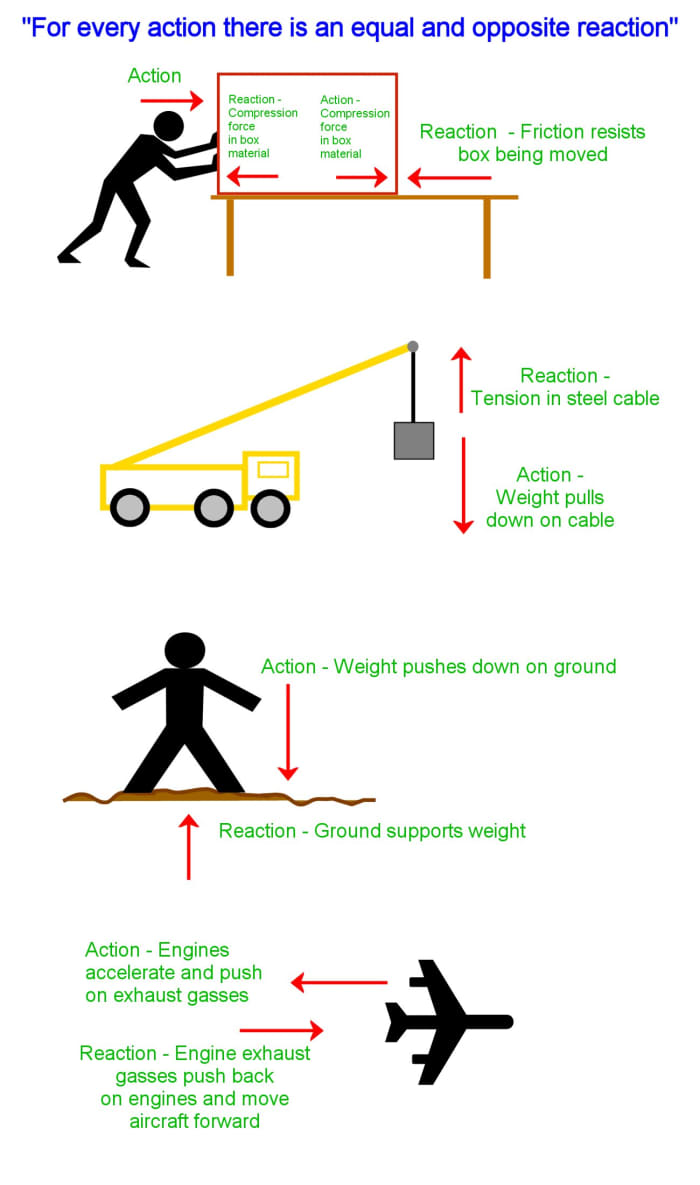

3. Newton's Third Law of Motion: Action and Reaction

This means that when a force is exerted on an object, the object pushes back.

Some examples:

- When you push on a spring, the spring exerts a force back on your hand. If you push against a wall, the wall pushes back.

- When you stand on the ground, the ground supports you and pushes back up. If you try to stand on water, the water cannot exert enough force and you sink.

- Foundations of buildings must be able to support the weight of the construction. Columns, arches, trusses and suspension cables of bridges must exert enough reactive compressive or tensile force to support the weight of the bridge and what it carries.

- When you try to slide a heavy piece of furniture along the floor, friction opposes your effort and makes it difficult to slide the object

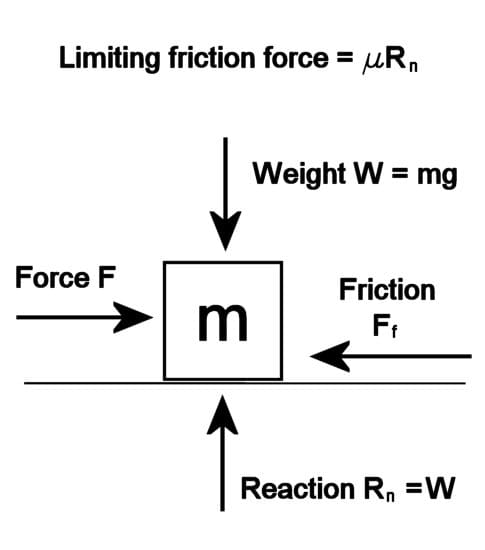

What is Dry Friction or "Stiction"?

As we saw above, friction is an example of a force. When you attempt to slide a piece of furniture along a floor, friction opposes your effort and makes things more difficult. Friction is an example of a reactive force, and doesn't exist until you push the object (which is the active force). Initially, the reaction balances the applied force i.e. your effort pushing the furniture, and there is no movement. Eventually, as you push harder, the friction force reaches a maximum, known as the limiting force of friction. Once this value is exceeded by the applied force, the furniture will start to slide and accelerate. The friction force is still pushing back and this is what makes it so difficult to continue to slide the object. This is why wheels, bearings, and lubrication come in useful as they reduce friction between surfaces, and replace it by friction at an axle and leverage to overcome this friction. Friction is still necessary to stop a wheel sliding, but it doesn't oppose motion. Friction is detrimental as it can cause overheating and wear in machines resulting in premature wear. So engine oil is important in vehicles and other machines, and moving parts need to be lubricated.

|

Forces acting on a mass when a force attempts to slide it along a surface. When the mass is just about to slide, the friction force Ff reaches a maximum value μRn. © Eugene Brennan |

Dry static friction, also known as stiction (see above diagram)

If F is the applied force on a body

The mass of the body is m

Weight of the body is W = mg

μs is the coefficient of friction (low μ means the surfaces are slippery)

and Rn is the normal reaction. (the reaction force acting upwards at right angles to the surface due to the weight of the object acting downwards)

If the surface is horizontal, then

Reaction Rn = Weight W

Then

limiting friction force is Ff = μsRn = μsW = μsmg

Remember this is the limiting force of friction just before sliding takes place. Before that, the friction force equals the applied force F trying to slide the surfaces along each other, and can be anything from 0 up to μRn.

So the limiting friction is proportional to the weight of an object. This is intuitive since it is harder to get a heavy object sliding on a specific surface than a light object. The coefficient of friction μ depends on the surface. "Slippery" materials such as wet ice and Teflon have a low μ. Rough concrete and rubber have a high μ. Notice also that the limiting friction force is independent of the area of contact between surfaces (not always true in practice)

Kinetic Friction

Once an object starts to move, the opposing friction force becomes less than the applied force. The friction coefficient in this case is μk.

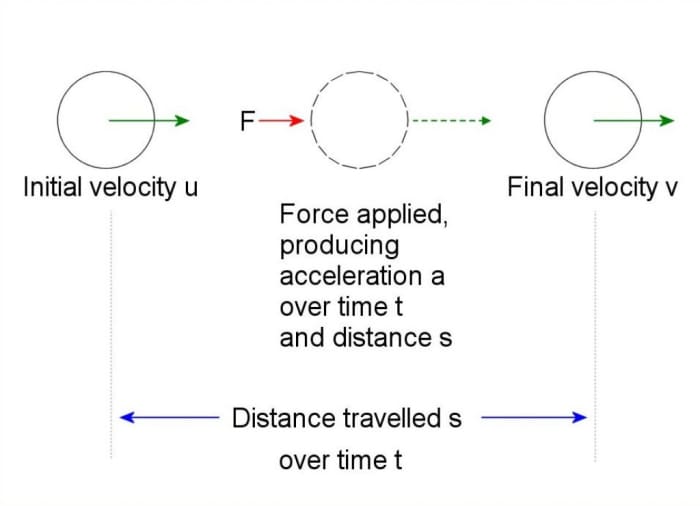

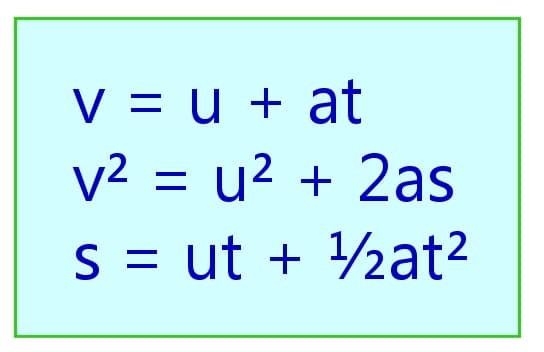

What Are Newton's Equations of Motion? (Kinematics Equations)

There are three basic equations which can be used to work out the distance travelled, time taken and final velocity of an accelerated object.

First let's pick some variable names:

u is the initial velocity

v is the final velocity

s is the distance covered

t is the time taken

and a is the acceleration produced by force F

As long as the force is applied and there are no other forces, the velocity u increases uniformly (linearly) to v after time t.

|

Acceleration of body. Force applied produces acceleration a over time t and distance s.© Eugene Brennan |

So for uniform acceleration we have three equations:

v = u + at

s = ut + 1/2 at2

v2 = u2 + 2as

Examples:

(1) A force of 100 newtons accelerates a mass of 5 kg for 10 seconds. If the mass is initially at rest, calculate the final velocity.

Firstly it is necessary to calculate the acceleration.

F = 100 newtons

m = 5 kg

F = ma so a = F/m = 100/5 = 20 m/s2

Next work out the final velocity, knowing the acceleration:

Substitute for u, a and t:

u = initial velocity = 0 since the object is at rest

a = 20 m/s2

t = 10 s

v = u + at = 0 + 20 x 10 = 200 m/s

(2) A mass of 10 kg is dropped from the top of a building which is 100 metres tall. How long does it take to reach the ground?

In this example, in theory it doesn't make any difference what the value for the mass is, the acceleration due to gravity is g irrespective of the mass. Galileo demonstrated this when he dropped two balls of equal sizes but differing masses from the leaning tower of Pisa. However in reality, the drag force due to air resistance will slow down the falling mass, so a 10 kg sheet of timber would fall slower than a 10 kg lead weight. So assume there is no drag and the calculations apply to a weight falling in a vacuum.

We know s = 100 m

g = 9.81 m/s2

u = 0 m/s

We can use the equation s = ut + 1/2 at2

The acceleration a in this case is the acceleration due to gravity so a = g

Therefore substituting for u and g gives

s = 0t +1/2 gt2 s = 1/2gt2

Rearranging

t = √(2s/g) = √(2 x 100) / 9.81 = 4.5 seconds approx

|

| Newton's equations of motion. © Eugene Brennan |

The Hammer and Feather Experiment From Apollo 15

Related Reading

Solving Projectile Motion Problems - Applying Newton's Equations of Motion to Ballistics

How Do Wheels Work? - The Mechanics of Axles and Wheels

Recommended Books

Mechanics

Applied Mechanics by John Hannah and MJ Hillier is a standard text book for students taking Diploma and Technician courses in engineering. It covers the basic concepts I briefly cover in this article as well as as other topics such as motion in a circle, periodic motion, statics and frameworks, impulse and momentum, stress and strain, bending of beams and fluid dynamics. Worked examples are included in each chapter in addition to set problems with answers provided.

Mathematics

Engineering Mathematics by K.A. Stroud is an excellent math textbook for both engineering students and anyone with an interest in the subject. The material has been written for part 1 of BSc. Engineering Degrees and Higher National Diploma courses.

A wide range of topics are covered including matrices, vectors, complex numbers, calculus, calculus applications, differential equations, series, probability theory, and statistics. The text is written in the style of a personal tutor, guiding the reader through the content, posing questions, and encouraging them to provide the answer.

This book basically makes learning mathematics fun!

References

Hannah, J. and Hillerr, M. J., (1971) Applied Mechanics (First metric ed. 1971) Pitman Books Ltd., London, England.

If you liked this article, you may be interested in reading more articles about mechanics:

Solving Projectile Motion Problems - Applying Newton's Equations of Motion to Ballistics

How Do Wheels Work? - The Mechanics of Axles and Wheels

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualised advice from a qualified professional.

© 2012 Eugene Brennan

No comments:

Post a Comment